The Unbearable Sadness of the Beefcake

On The Iron Claw and the invulnerable action star.

We are living in an era of sad boys with big thighs.

The Iron Claw and the Von Erich family might mean nought to audiences who are not familiar with wrestling and its cultural place in 1980s Americana, so the film must succeed by two different metrics: the biopic and the sports movie. The first is measured by its accuracy (how close is the fiction to the facts); the second, by the emotional swell of competition (do our heroes win or lose).

Nobody wins in The Iron Claw.

Instead, director Sean Durkin strips away any leftover idealisation of the Great Big American Wrestler to focus the disproportionate tragedy that befalls as family where every boy tries to fit into a single-issue mould of masculinity.

There is no room for pleasure or beauty in the Von Erich house. The patriarch, Fritz Von Erich (Holt McCallany) is from the grunt-and-endure school of manliness, and from the moment his children are old enough to walk he begins training them into the family business. His pride in his sons is based entirely on their size, strength and their success as athletes. “Now, we all know Kerry's my favourite, then Kev, then David, then Mike. But the rankings can always change,” he tells them over breakfast (a little trauma goes well with scrambled eggs). Though their father keeps pushing them to compete against one another, the Von Erich boys are only at ease in the world when they’re together: Kevin (Zac Efron) is following in his father’s footsteps into professional wrestling; Kerry (Jeremy Allen White) is on his way to becoming an Olympian; David (Harris Dickinson) has the gift of the gab; and Mike (Stanley Simmons), unfortunately, is gifted musically, not athletically.

The Iron Claw’s sadness runs deep in the family, and most of all, in Kevin. Out of the five1 brothers, only one will survive. Their father taught them that if they were the strongest, nothing could hurt them. He was wrong.

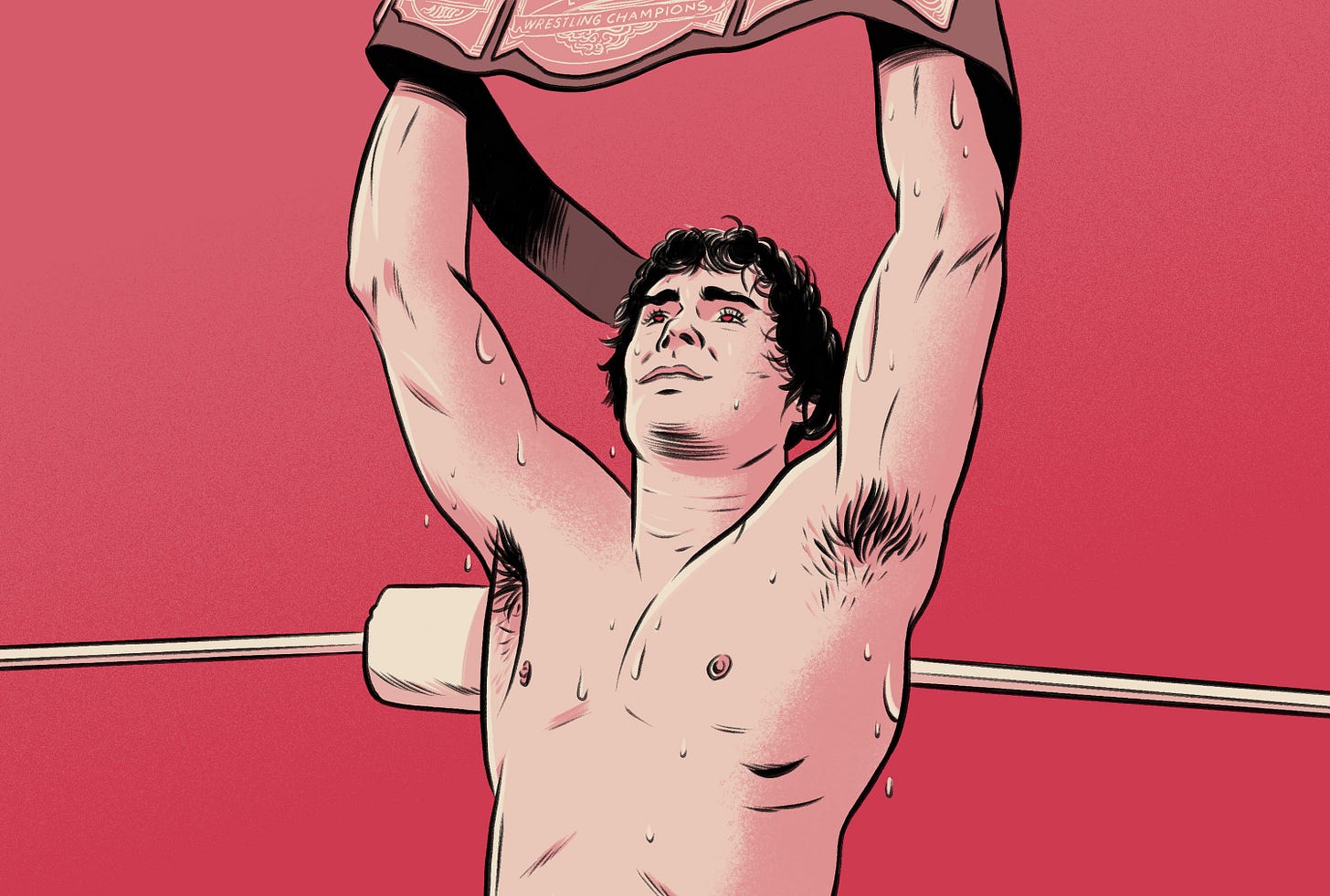

In The Iron Claw, the Von Erich brothers seem to exist in bodies that are only tools for winning. When Kevin wakes up, skin so taut that it looks drawn on, veins bulging with effort, he immediately goes for a run. His body looks like it hurts, all the time. Every waking moment must be concerned with effort, productivity, strain. During his first fight for the World Championship2, Kevin gets knocked out of the ring and struggles to climb back in. Later on, he practices falling down on the mat so this delay does not happen again. The camera stays close to ground while he lands on his back, over and over again. I thought of many things during that scene but mostly it was a variation of therapy for the boys and honey, please stretch. (Spoiler alert: The Iron Claw contains not a moment of stretching.)

And all I wanted was to look at some strongmen throw each other around a bit.

The playfulness of the film’s cast, mostly current or former thirst objects, sits in direct contrast to the bleakness of the film itself. The beefcake is supposed to be a fun stock character: a big, muscly man; often posing or lifting comically heavy things; a beautiful show-off, meant to be ogled and admired. The beefcake’s game was always size: the bigger you are, more of a man you are; if you couldn’t be tall, you could be wide. Self-actualisation, one pump at a time.

You’ll find the seeds of beefcake cinema in the use of athletes as movie stars in the 1930s: Johnny Weissmuller, a two-time Olympic swimmer, became the star of Tarzan across twelve movies 1932 to 1948, and after that, the Jungle Jim film and TV series; and Buster Crabbe, who played Tarzan, Flash Gordon and a myriad of other “jungle men” roles that often involved him taking his shirt off.

Later on, in the 1950s, fitness and “male physique” magazines were on the rise, ostensibly for educational purposes3. Their bodies were objects of beauty. There is a wholesome air about these images now: beautiful men in loin-clothes, posing in over-wrought scenarios that would add a bit of whimsy to the pictures. The docudrama Beefcake (1998) chronicles the life of photographer and pornographer Bob Mizer, whose work would be a staple for gay readers.

The bodybuilders, meanwhile, were a new kind of freak show. Concentrated largely around Muscle Beach in Santa Monica, California, bodybuilders would show-off their physique for tourists, onlookers and share fitness tips. This small but extremely competitive world attracted mainstream attention with the release of Pumping Iron (1977), which plays out like the best sports documentaries do: a group of hyper-obsessives whose entire sense of self in enveloped in a world they create for themselves. Serving maximum cunt, a young Arnold Schwarzenegger is the default anti-hero of the film, strolling through Gold’s Gym gleefully receiving the adoration of his fellow beefcakes. The newcomer on the scene, Lou Ferrigno, is determined to beat his hero on the Mister Olympia podium (itself a competition that feels invented by beefcakes in order to justify all the pumping). Both of them would become movie stars: Ferrigno was Hulk and Hercules (1983) and Schwarzenegger, well, he was Schwarzenegger. Together with New York-bred Sylvester Stallone, the two muscle-men would dominate 1980s Hollywood action cinema, along with martial artists Jean-Claude Van Damme, Jackie Chan, Chuck Norris, and Dolph Lundgren. It was an era of undefeatable bodies. They hit, they got hit, and they always got back up.

In the superhero era, bodies have aided this unbeatability with a sci-fi twist or supernatural sprinkle. There’s now a magical reason why someone is super-strong and impervious to harm. This gives the illusion of effortlessness, like their “impossibly lean, shockingly muscular, with magnificently coiffed hair, high cheekbones, impeccable surgical enhancements, and flawless skin” are merely gifts from the movie gods, bestowed upon a select few. Even the non-super action heroes are seemingly immune to death (I see you, John Wick and Dom Toretto).

A lot of the coverage of The Iron Claw has focused on former teen heartthrob Zac Efron mutation into the beastly-sized Von Erich. The rigour of training, weight gain and loss, and physical transformation are the backbone of an Oscar campaign. They are embodiments of an actor’s effort and, as such, they demand recognition.

There is something jarring about the way we have built a culture dissecting the body of an actor, separate from the role they are building the physique for. A Men’s Health profile of Efron in 2022 starts with a drooling description of his arms before moving into the physical and psychological effects maintaining that Baywatch had on him. In that piece, Efron wonders about “what it would be like to not have to be in shape all the time.” Observing famous bodies has become a cottage industry. The videos and covers analysing celebrity workouts in turn breed videos and articles debunking their workouts. Personal trainers have become celebrities in their own right, all peddling the same promise of transformation. A light Google will show you Efron’s exact training regime.

It worked, evidently, but a jacked body does not equal a good performance. Kevin Von Erich’s physicality is most useful in the quiet moments, out of the ring. In the scene where Kevin meets his future wife Pam (Lily James, forever stuck playing someone’s supportive girlfriend/wife) after a match: he wobbles out to sign some autographs, one of his eyes swollen shut; she can barely stand still while she ogles him. Kevin remains totally clueless while she flirts, almost uncomfortable at the idea of being looked up on desirously. This is one of the most delicate moments of Efron’s performance, especially poignant coming from an actor who has been sexualised since his High School Musical days.

Efron’s most impressive stunt is not the amount of muscle he’s put on, but the discomfort and stiffness that radiates through every one of his moves, the way Kevin’s shoulders harden when his father enters a room, and how he only seems limber when he’s playing with his brothers.

Far from invulnerable, the Von Erich’s carry themselves with pained effort. Even during the obligatory montage of their domination of the wrestling world, we see muscles in gloomy close-up, flexing and sweating. All around them hangs an air of unavoidable tragedy that no amount of upside-down push-ups can stave off. Their bodies are often showed bruised, bleeding, on ice. Always insufficient.

A sixth Von Erich brother was excised from the film because it felt like too much tragedy for one film.

Championship of something. Don’t come at me, it’s all made-up anyway.

I love to be educated.